How do cells stay the right size?

Cells maintain a characteristic size that allows them to function properly. For instance, red blood cells are much smaller than most human cells so they can squeeze through tiny blood vessels, while neurons can grow over a meter long to send signals across the body. In healthy tissues, cells of the same type are usually very similar in size.

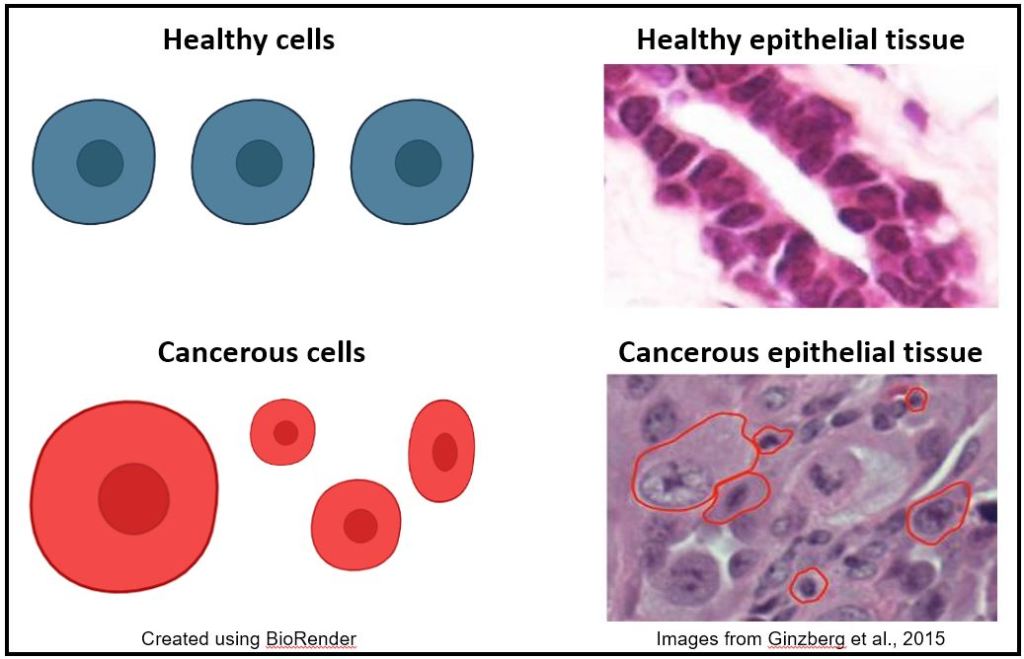

In cancer, this tight control of size is often lost. Abnormal cell size—either much larger or smaller than normal—is a hallmark of many cancers and is used by pathologists to help diagnose the disease (see figure below). These changes in size reflect disruptions in how cancer cells grow and divide.

To maintain proper size, cells—from simple organisms like yeast to humans—typically grow to a certain size before dividing. This means that cells must be able to sense their own size and use that information to control their progression through the cell cycle. However, the exact mechanisms cells use to measure their size—and what aspect of cell geometry they are measuring (such as length, surface area, or volume) are still not well understood.

Understanding how cells sense and control their size will not only help us learn more about normal cell biology but also shed light on how these processes break down in cancer, potentially revealing new targets for diagnosis or treatment.

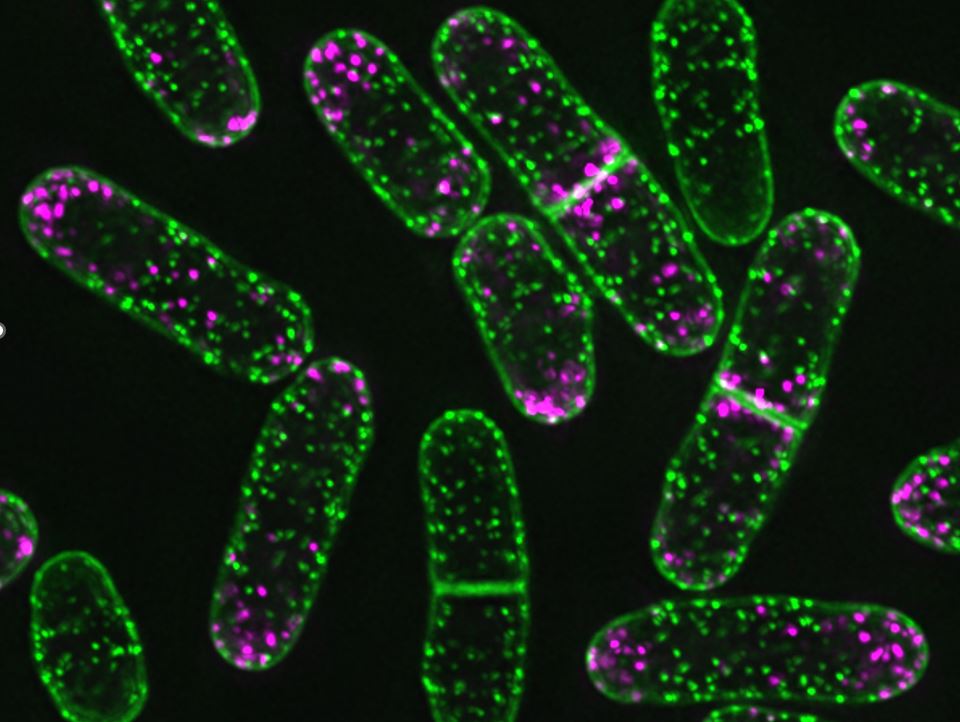

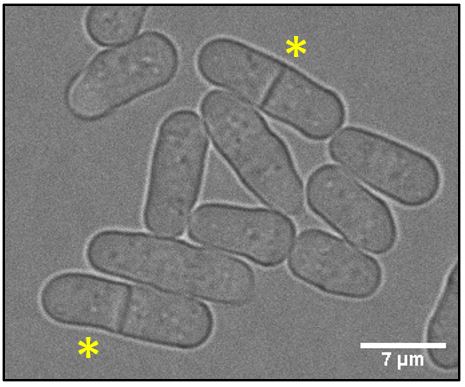

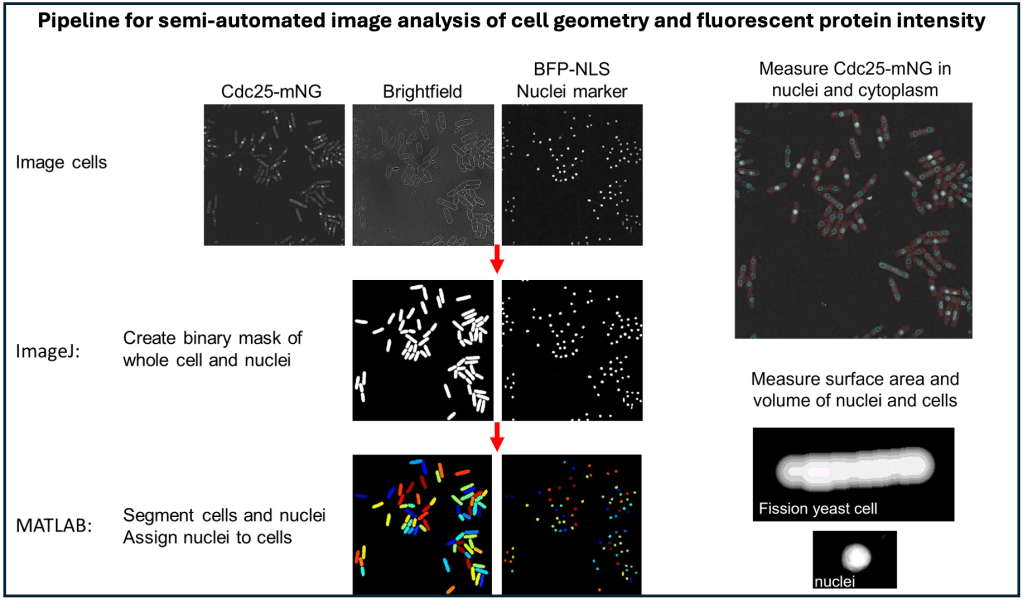

We use fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe as a model organism to study cell size control because they are a eukaryotic single celled organism that uses the same genes and proteins as human cells do to control cell division. They have a simple rod shape and rapid cell cycle making it easy to measure cell growth and cell size by live-cell microscopy. There are also extensive genetic resources, including fission yeast mutants with altered cell size. It is also very easy to delete genes and integrate tags to visualize proteins by live cell microscopy or detect proteins on western blots.

Brightfield image of Fission yeast cells. *Asterisks point out dividing cells.

Questions we are addressing:

- What molecular pathways link cell cycle components to cell size or growth to achieve cell size control?

- How do cells control their size when they encounter environmental stress?

How do cells stay the right shape?

Most cells maintain a specific shape in order to perform their specialized functions. For example, neurons have a highly distinctive structure that enables them to transmit signals in one direction—from dendrites to axons. This shape isn’t random; it is actively maintained by directing growth to specific regions of the cell while preventing growth in others.

This process is called cell polarity—the ability of a cell to organize its shape and internal components in a spatially controlled way. Polarity involves asymmetric distribution of proteins and structures, and it plays a key role in processes such as cell migration, tissue organization, and development. Importantly, many of the core proteins that regulate polarity are conserved from yeast to humans.

Fission yeast is a powerful model system for studying cell polarity because of its simple, rod shape and tightly controlled growth pattern. Insights gained from this system have advanced our understanding of how cells establish and maintain polarity.

Disruption of cell polarity is a common feature in diseases such as cancer, where the loss of organized structure can contribute to uncontrolled growth, invasion, and metastasis. Studying the basic biology of polarity in simple systems like yeast can therefore provide valuable clues to how these processes go awry in human disease.

Questions we are addressing:

- How do cells stay the right shape when they encounter environmental stress?

- What molecular pathways coordinate spatial and temporal regulation of cell shape?